Foto: Jane Bown

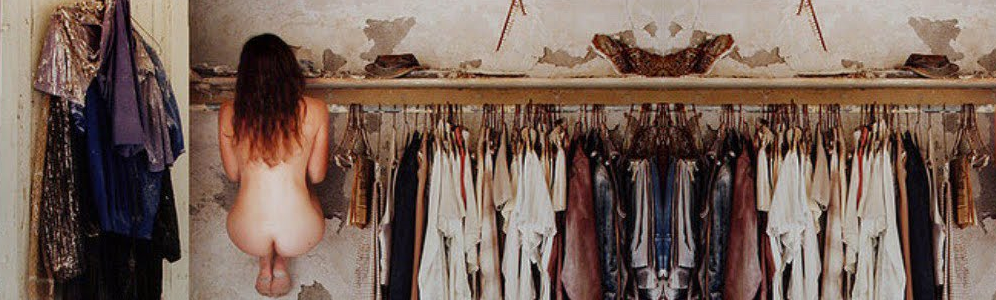

¿De qué están hechas las chicas

grandes?

La construcción de una mujer:

una mujer no está hecha de carne,

de hueso y nervio,

de vientre, pechos, hígado, codos y

dedos de los pies.

Se manufactura como un auto

deportivo.

Se remodela, reajusta y rediseña

todas las décadas.

Cecilia en la universidad había

sido la seducción misma.

Se retorcía entre las barras como

una anguila de seda,

con las caderas y el culo que eran

una promesa, y la boca

fruncida con el labial rojo oscuro

del deseo.

Nos visitó en el 68 y todavía usaba

pollera

ajustada hasta la rodilla y el

mismo labial rojo oscuro,

mientras yo bailaba por Manhattan en minifalda

con los labios pálidos como leche de

damasco

y el pelo suelto como las crines de

una yegua. Oh, queridas,

¿Me creí superior en ese momento,

le pasara lo que le pasara a la

pobre Cecilia?

Ella ya estaba fuera de moda, fuera de

juego,

descalificada, desdeñada, des-

membrada del club del deseo.

Miren las fotos de las revistas de

moda

francesas del siglo XVIII:

el siglo de la última fantasía para

damas

forjada en seda y corsés.

El miriñaque les corría la cadera

un metro

para cada lado, la cintura

apretada,

la panza comprimida por las

maderas.

Los pechos con relleno abajo y a

los costados

servidos como manzanas en un bol.

El piecito preso en una zapatilla

que

jamás fue pensada para caminar.

Y arriba de todo un colosal dolor

de cabeza:

el pelo como pieza de museo,

ornamentado

a diario con cintas, grutas y

floreros,

montañas y fragatas en plena

navegación, globos y lobos, al

capricho

de un peluquero desatado.

Los sombreros eran tortas de

casamiento rococó

que le hubieran hecho sombra al

Strip de Las Vegas.

He aquí a una mujer en forma

con el exoesqueleto torturándole la

carne:

una mujer hecha de dolor.

¡Y ahora qué superiores somos!

Miren a la mujer

moderna:

delgada como cuchilla de tijera.

Corre todas las mañanas en una

cinta,

se mete a gruñir y tironear

en una máquina de pesas y poleas,

con una imagen en mente a la que

nunca

se podrá aproximar, un cuerpo de

vidrio

rosa que nunca se arruga,

nunca crece, nunca desaparece. Se

sienta

a la mesa y cierra los ojos a la

comida

con hambre, siempre con hambre:

una mujer hecha de dolor.

Un perro o un gato se acercan,

se huelen el hocico. Se olfatean el

culo.

Se gruñen o se lamen. Se enamoran

tan seguido como nosotras,

y con la misma pasión. Pero ellos

se enamoran

o se apasionan a pelo,

sin miriñaque ni corpiño con push

up

sin extirparse una costilla ni

hacerse liposucción.

No es para los perros, ni machos ni

hembras,

que los caniches se podan

como macizos topiarios.

Si solamente pudiéramos gustarnos

en bruto los unos a los otros.

Si solamente pudiéramos querernos a

nosotras mismas

como queremos a un bebé que nos

balbucea en los brazos.

Si no nos programaran y nos reprogramaran

para necesitar lo que nos venden.

¿Por qué íbamos a querer vivir en

una propaganda?

¿Por qué íbamos a querer

flagelarnos las blanduras

hasta hacerlas líneas rectas como

un cuadro de Mondrian?

¿Por qué nos íbamos a castigar con

el desprecio,

como si tener grande el culo

fuera peor que la codicia o la

maldad?

¿Cuándo vamos a dejar las mujeres

de estar obligadas

a ver nuestros cuerpos como

experimentos de ciencias,

como jardines que hay que

desmalezar

como perros que hay que domesticar?

¿Cuándo una mujer va a dejar

de estar hecha de dolor?

Las implicancias del uno más uno

A veces colisionamos, placas

tectónicas que se funden,

continentes que empujan y se

derrumban en las venas

de fuego derretido del centro de la

tierra y hacen saltar

montones de rocas hasta las crestas

dentadas de la Sierra.

A veces tus manos van a la deriva,

caricias de la

punta de un ala como el penacho

sedoso de la asclepia,

y nuestros labios pacen y una

corriente de deseos se congrega

como la bruma sobre el calor del

agua hasta que se hace lluvia.

A veces con fervor vamos cavando y

excavando, gruñendo y arrojando las

sábanas

como si fueran tierra suelta,

metiendo la nariz caliente

en la carne del otro y

revolcándonos.

A veces somos dos chicos

besuqueándonos como tontos

sobre la manta, haciéndonos

cosquillas en el xilofón de la columna

y chistes sucios, a gritos, como todo un

pijama party

que salta y rebota hasta partir la

cama en dos.

Te doy vueltas y vueltas alrededor

otras veces, explorando

a los tumbos, buscando una salida

del laberinto de los bojes altos

en el que entro corriendo con los

pulmones a punto de

reventar, rumbo a la fuente de

fuego verde del corazón.

A veces te abrís de par en par como

las puertas de una catedral

y me empujás adentro. A veces te

deslizás

dentro de mí como una víbora en su

nido.

Y a veces entrás marchando con una

banda de bronces.

Diez años de encastrar cuerpo con

cuerpo

y todavía entonan cantos salvajes

en nuevos tonos.

Es más y menos que el amor: es

ritmo,

química, magia, voluntad, y suerte.

Uno más uno es igual a uno, no se

puede saber si no es

en el momento, no se traduce en

palabras,

no es explicable ni filosóficamente

relevante.

Pero es. Y es. Y es. Amén.

Muñeca Barbie

Esta nena nació como se suele

nacer,

le ofrecieron muñecas que hacían

pipí,

planchas, cocinas BGH en miniatura

y

lápices labiales diminutos de color

caramelo de cereza.

Después, en la magia de la

pubertad, una compañera dijo:

Tenés la nariz muy grande y las

piernas gordas.

Ella era sana, probadamente

inteligente,

tenía espalda y brazos fuertes,

abundante instinto sexual y

destreza manual.

Anduvo de acá para allá pidiendo

disculpas.

Todos veían una nariz grande sobre

dos piernas gordas.

Le aconsejaron que se hiciera la

tímida,

la exhortaron a volverse simpática,

a hacer ejercicio y dieta, a

sonreír y engatusar.

Como la correa de un ventilador,

así

se le gastó el buen humor.

Entonces se cortó la nariz y las

piernas

y se las ofreció.

La exhibieron en un féretro forrado

de seda

maquillada con cosméticos

funerarios,

una naricita respingada,

un camisón rosa y blanco.

¿No está preciosa?, dijeron todos.

¡La consumación, era hora!

A toda mujer le llega su final

feliz.

La canción del gato

Mía, dice el gato, sacando una pata

de la oscuridad.

Mi amante, mi amiga, mi esclava, mi

juguete, dice

el gato, haciéndote en el pecho el

gesto de exprimir

la leche de las tetas olvidadas de

la madre.

Vamos a caminar al bosque, dice el

gato.

Voy a enseñarte a leer el diario de

los aromas,

a desaparecer entre las sombras, a

esperar como espera una trampa, a cazar.

Te dejo este ratón calentito

en la alfombra.

Vos me alimentás, yo trato de

alimentarte, dice el gato,

para eso somos amigos, aunque yo

sea más imparcial.

¿Podés saltar veinte veces lo que

mide tu cuerpo?

¿Podés subir y bajar corriendo de

un árbol? ¿Y saltar entre los techos?

Vamos a frotarnos y a hablar de las

caricias.

Tengo emociones puras como

cristales de sal, e igual de duras.

Como mis ojos, relucen mis

lujurias. A la mañana te canto

dando vueltas y vueltas por tu cama

y por tu cara.

Vení, voy a enseñarte a bailar con

tanta naturalidad

como dormir o caminar o estirarte

largo, largo.

Con los bigotes hablo del miedo, y

del orgullo con las garras.

La envidia me agita la cola. El

amor me habla entero: una palabra

hecha de pelos. Te voy a enseñar a

estar quieta como un huevo

y a deslizarte por el pasto como el

fantasma del viento.

El cumpleaños del mundo

En el cumpleaños del mundo

empiezo a considerar

lo que hice y lo que dejé

de hacer, pero este año

no hay tanta reconstrucción

de mi psiquis con daño

permanente, apuntalando amistades

erosionadas, desenterrando los

tocones de antiguos resentimientos

que se niegan a arraigar por su

cuenta.

No, este año me quiero llamar

a mí misma y amonestarme por

lo que hice y por lo que no hice

por la paz. ¿Cuánto me atreví

a oponerme?

¿Cuánto puse

en juego por la libertad?

La mía y la de los otros.

Mientras a esas libertades las pelan,

pican y rebanan, ¿dónde

me pronuncié? ¿A quién

traté de movilizar? En

esta estación sagrada, me pongo de

pie

para autocondenarme por mi pereza

en una época en la que las mentiras

asfixian

la mente y la retórica

somete la razón al deslizarse

de sus boas constrictoras. Aquí

me paro ante las puertas

abiertas, ante el fuego que

me encandila, y mientras me

aproximo

a lo que me juzga, me juzgo

yo. Denme las armas

de destrucción mínima. Dejen que

mis palabras se transformen en

chispas.

Más que suficiente

El primer lirio de junio abre la

boca roja.

En el camino de arena por el que

vamos,

la rosa multiflora trepa a los

árboles y cae

en cascadas de flores blancas o

rosas. La escena,

intensa y simple, se deja llevar

como la niebla de colores.

La punta de flecha esparce sus

racimos

de flores cremosas, y las zarzamoras

florecen en los matorrales. La estación de

la alegría para las abejas. El verde

nunca más va a

volver a ser tan verde, tan puro,

nuevo y

exuberante, el pasto eleva sus

inflorescencias

al viento. Vino fresco y rico de

junio,

en vos nos internamos tambaleando,

sucios de polen y victoriosos, como la

tortuga

que deposita sus huevos al costado

de la ruta.

Promesas de invierno

Tomates rozagantes como las

nalgas perfectas de los bebés,

berenjenas brillosas como

guardabarros lustrados,

ajíes impecables de neón

violeta

y reluciente, chauchas trepadoras prolíficas

que crecen como el tallo de Jack

bajo los efectos del Viagra,

grandes como ruedas de camión, las

zinias que el hongo

nunca marchita, las rosas colgadas

de un arbusto que el chancro jamás

tocó,

los arbolitos frutales valientes

que ladean

sus adornos inmaculados de frutas

de vidrio:

estoy acostada en el sofá, cubierta

de catálogos de semillas, queriendo

comprar

demasiadas. Por la ventana

cae

aguanieve y un viento ribeteado de

cuchillos de hielo se mete por cada

hendija.

Miéntanme, mercaderes de jardines:

Quiero creer en todas las promesas,

creer en tomates de dos kilos

y en dalias más brillantes que el

sol

que se comió la escarcha hace unos

días.

El amigo

Nos sentamos uno de cada lado de la

mesa.

él dijo: cortate las manos.

siempre están hurgando algo.

me van a tocar.

Dije que sí.

La comida se enfriaba en la mesa.

él me dijo: quemate el cuerpo.

no está limpio y tiene olor a sexo.

Irrita mi úlcera mental.

Dije que sí.

Te amo, me dijo.

Es muy lindo, dijo.

Me gusta que me ames,

me hace feliz.

¿Ya te cortaste las manos, no?

Los colores que nos atraviesan

Morado como los tulipanes de mayo,

malva

en el terciopelo suntuoso, morado

como las manchas que dejan las

moras

en los labios, y en las manos,

el morado de las uvas maduras

soleadas y tibias como la carne.

Todos los días voy a darte un

color,

como si pusiera una flor en un

florero

de tu escritorio.

Todos los días

te voy a pintar, como se

pintan

las mujeres entre ellas

con henna las manos y los pies.

Rojo como el henna, como la canela,

como las ascuas después de que el

fuego se amontona,

como el cardenal en su comedero

y las rosas que caen de la glorieta

con su peso inclinando las maderas

o el rojo del jarabe que hago con

los pétalos.

Naranja como la fruta perfumada

que cuelga sus globos del árbol

resplandeciente,

naranja como las calabazas en la

tierra,

como las asclepias y las mariposas

monarca

que vienen a alimentarse de ellas,

naranja como mi

gato que corre ágil por el pasto

crecido.

Amarillo como los ojos sabios y

bellacos de una cabra.

Amarillo como una colina de

narcisos,

amarillo como los dientes de león

en la ruta,

amarillo como la manteca y la yema

de huevo,

amarillo como el micro escolar que se

detiene adelante

amarillo como un impermeable abajo del

chaparrón.

Acá está mi ramo, acá hay una

canción

por cada cosa que hacés y en la que

me hacés pensar, acá está la

plegaria

indirecta a tu altura, a tu

profundidad

y también a tu amplitud.

Acá está mi caja de crayones nuevos,

a tus pies.

Verde como la jalea de menta, verde

como una rana sobre el temblor de

un nenúfar,

el verde de la lechuga romana,

erguida,

a punto de huir de su torre

opulenta,

verde como el Grand Chartreuse en

un vaso

transparente, verde como las

botellas de vino.

Azul como las violetas, los

delfinios,

la centáurea.

Azul como el roquefort,

como el Saga,

como el agua quieta.

Azul como los ojos de un gato

siamés.

Azul como las sombras en la nieve

reciente, como el cielo

de la primavera que bebe de un charco

del asfalto.

Cobalto como el cielo a medianoche

cuando el día se va sin dejar huella

y nos quedamos, una en brazos de la

otra,

con los ojos cerrados y los dedos

abiertos

y todos los colores del mundo pasan

a través de nuestros cuerpos como

si fueran cuerdas de fuego.

El siete de oros

Bajo un cielo color sopa de arvejas

ella mira allá afuera cómo crece su trabajo

frondoso, activo, como la vid o la chaucha trepadora

como crecen las cosas del mundo real, tomándose su tiempo.

Si se las cuida de la forma adecuada, si se fertilizan, si se riegan,

si en invierno se les brinda refugio y alimento a los pájaros que se comen los insectos,

si brilla el sol y se quitan las orugas,

si vienen la mantis religiosa, la vaquita de San Antonio y las abejas,

entonces las plantas florecen, cada una según su reloj interior.

Las conexiones se hacen lentamente, a veces crecen bajo tierra

y no siempre se sabe lo que pasa con solo mirar.

Más de la mitad del árbol se extiende bajo el suelo que pisamos.

Entrá en silencio como la lombriz que no hace alardes.

Luchá con la persistencia de la peste que derriba el árbol.

Dispersate como la calabaza que invade el jardín.

Roé en la oscuridad, y con el sol fabricá azúcar.

Tejé conexiones auténticas, creá nodos auténticos, construí casas auténticas.

Viví una vida que puedas tolerar: hacé el amor que sea amoroso.

Seguí tejiendo, entretejiendo y asimilando más,

una selva de zarzas y espesura para el afuera pero para nosotras

conectada con las corridas, madrigueras y escondites de los conejos.

Viví como si te gustaras a vos misma, y puede ser que suceda:

tendé la mano, seguí tendiendo la mano, incorporá,

así vamos a vivir un tiempo largo: no para siempre,

porque todo jardinero sabe que después de cavar, después de sembrar

después de una temporada larga de atención y crecimiento, llega la cosecha.

Versiones en castellano de Sandra Toro.

What are Big Girls Made of?

The construction of a woman:

a woman is not made of flesh

of bone and sinew

belly and breasts, elbows and liver and toe.

She is manufactured like a sports sedan.

She is retooled, refitted and redesigned

every decade.

Cecile had been seduction itself in college.

She wriggled through bars like a satin eel,

her hips and ass promising, her mouth pursed

in the dark red lipstick of desire.

She visited in '68 still wearing skirts

tight to the knees, dark red lipstick,

while I danced through Manhattan in mini skirt,

lipstick pale as apricot milk,

hair loose as a horse's mane. Oh dear,

I thought in my superiority of the moment,

whatever has happened to poor Cecile?

She was out of fashion, out of the game,

disqualified, disdained, dis-

membered from the club of desire.

Look at pictures in French fashion

magazines of the 18th century:

century of the ultimate lady

fantasy wrought of silk and corseting.

Paniers bring her hips out three feet

each way, while the waist is pinched

and the belly flattened under wood.

The breasts are stuffed up and out

offered like apples in a bowl.

The tiny foot is encased in a slipper

never meant for walking.

On top is a grandiose headache:

hair like a museum piece, daily

ornamented with ribbons, vases,

grottoes, mountains, frigates in full

sail, balloons, baboons, the fancy

of a hairdresser turned loose.

The hats were rococo wedding cakes

that would dim the Las Vegas strip.

Here is a woman forced into shape

rigid exoskeleton torturing flesh:

a woman made of pain.

How superior we are now: see the modern woman

thin as a blade of scissors.

She runs on a treadmill every morning,

fits herself into machines of weights

and pulleys to heave and grunt,

an image in her mind she can never

approximate, a body of rosy

glass that never wrinkles,

never grows, never fades. She

sits at the table closing her eyes to food

hungry, always hungry:

a woman made of pain.

A cat or dog approaches another,

they sniff noses. They sniff asses.

They bristle or lick. They fall

in love as often as we do,

as passionately. But they fall

in love or lust with furry flesh,

not hoop skirts or push up bras

rib removal or liposuction.

It is not for male or female dogs

that poodles are clipped

to topiary hedges.

If only we could like each other raw.

If only we could love ourselves

like healthy babies burbling in our arms.

If only we were not programmed and reprogrammed

to need what is sold us.

Why should we want to live inside ads?

Why should we want to scourge our softness

to straight lines like a Mondrian painting?

Why should we punish each other with scorn

as if to have a large ass

were worse than being greedy or mean?

When will women not be compelled

to view their bodies as science projects,

gardens to be weeded,

dogs to be trained?

When will a woman cease

to be made of pain?

Implications of One plus One

Sometimes we collide, tectonic plates merging,

continents shoving, crumpling down into the molten

veins of fire deep in the earth and raising

tons of rock into jagged crests of Sierra.

Sometimes your hands drift on me, milkweed's

airy silk, wingtip's feathery caresses,

our lips grazing, a drift of desires gathering

like fog over warm water, thickening to rain.

Sometimes we go to it heartily, digging,

burrowing, grunting, tossing up covers

like loose earth, nosing into the other's

flesh with hot nozzles and wallowing there.

Sometimes we are kids making out, silly

in the quilt, tickling the xylophone spine,

blowing wet jokes, loud as a whole

slumber party bouncing till the bed breaks.

I go round and round you sometimes, scouting,

blundering, seeking a way in, the high boxwood

maze I penetrate running lungs bursting

toward the fountain of green fire at the heart.

Sometimes you open wide as cathedral doors

and yank me inside. Sometimes you slither

into me like a snake into its burrow.

Sometimes you march in with a brass band.

Ten years of fitting our bodies together

and still they sing wild songs in new keys.

It is more and less than love: timing,

chemistry, magic and will and luck.

One plus one equal one, unknowable except

in the moment, not convertible into words,

not explicable or philosophically interesting.

But it is. And it is. And it is. Amen.

Barbie Doll

This girlchild was born as usual

and presented dolls that did pee-pee

and miniature GE stoves and irons

and wee lipsticks the color of cherry candy.

Then in the magic of puberty, a classmate said:

You have a great big nose and fat legs.

She was healthy, tested intelligent,

possessed strong arms and back,

abundant sexual drive and manual dexterity.

She went to and fro apologizing.

Everyone saw a fat nose on thick legs.

She was advised to play coy,

exhorted to come on hearty,

exercise, diet, smile and wheedle.

Her good nature wore out

like a fan belt.

So she cut off her nose and her legs

and offered them up.

In the casket displayed on satin she lay

with the undertaker's cosmetics painted on,

a turned-up putty nose,

dressed in a pink and white nightie.

Doesn't she look pretty? everyone said.

Consummation at last.

To every woman a happy ending.

The Cat's Song

Mine, says the cat, putting out his paw of darkness.

My lover, my friend, my slave, my toy, says

the cat making on your chest his gesture of drawing

milk from his mother's forgotten breasts.

Let us walk in the woods, says the cat.

I'll teach you to read the tabloid of scents,

to fade into shadow, wait like a trap, to hunt.

Now I lay this plump warm mouse on your mat.

You feed me, I try to feed you, we are friends,

says the cat, although I am more equal than you.

Can you leap twenty times the height of your body?

Can you run up and down trees? Jump between roofs?

Let us rub our bodies together and talk of touch.

My emotions are pure as salt crystals and as hard.

My lusts glow like my eyes. I sing to you in the mornings

walking round and round your bed and into your face.

Come I will teach you to dance as naturally

as falling asleep and waking and stretching long, long.

I speak greed with my paws and fear with my whiskers.

Envy lashes my tail. Love speaks me entire, a word

of fur. I will teach you to be still as an egg

and to slip like the ghost of wind through the grass.

The Birthday of the World

On the birthday of the world

I begin to contemplate

what I have done and left

undone, but this year

not so much rebuilding

of my perennially damaged

psyche, shoring up eroding

friendships, digging out

stumps of old resentments

that refuse to rot on their own.

No, this year I want to call

myself to task for what

I have done and not done

for peace. How much have

I dared in opposition?

How much have I put

on the line for freedom?

For mine and others?

As these freedoms are pared,

sliced and diced, where

have I spoken out? Who

have I tried to move? In

this holy season, I stand

self-convicted of sloth

in a time when lies choke

the mind and rhetoric

bends reason to slithering

choking pythons. Here

I stand before the gates

opening, the fire dazzling

my eyes, and as I approach

what judges me, I judge

myself. Give me weapons

of minute destruction. Let

my words turn into sparks.

More than Enough

The first lily of June opens its red mouth.

All over the sand road where we walk

multiflora rose climbs trees cascading

white or pink blossoms, simple, intense

the scene drifting like colored mist.

The arrowhead is spreading its creamy

clumps of flower and the blackberries

are blooming in the thickets. Season of

joy for the bee. The green will never

again be so green, so purely and lushly

new, grass lifting its wheaty seedheads

into the wind. Rich fresh wine

of June, we stagger into you smeared

with pollen, overcome as the turtle

laying her eggs in roadside sand.

Winter Promises

Tomatoes rosy as perfect baby's buttocks,

eggplants glossy as waxed fenders,

purple neon flawless glistening

peppers, pole beans fecund and fast

growing as Jack's Viagra-sped stalk,

big as truck tire zinnias that mildew

will never wilt, roses weighing down

a bush never touched by black spot,

brave little fruit trees shouldering up

their spotless ornaments of glass fruit:

I lie on the couch under a blanket

of seed catalogs ordering far

too much.

Sleet slides down

the windows, a wind edged

with ice knifes through every crack.

Lie to me, sweet garden-mongers:

I want to believe every promise,

to trust in five pound tomatoes

and dahlias brighter than the sun

that was eaten by frost last week.

The Friend

We sat across the table.

he said, cut off your hands.

they are always poking at things.

they might touch me.

I said yes.

Food grew cold on the table.

he said, burn your body.

it is not clean and smells like sex.

it rubs my mind sore.

I said yes.

I love you, I said.

That’s very nice, he said

I like to be loved,

that makes me happy.

Have you cut off your hands yet?

Colors Passing Through Us

Purple as tulips in May, mauve

into lush velvet, purple

as the stain blackberries leave

on the lips, on the hands,

the purple of ripe grapes

sunlit and warm as flesh.

Every day I will give you a color,

like a new flower in a bud vase

on your desk.

Every day

I will paint you, as women

color each other with henna

on hands and on feet.

Red as henna, as cinnamon,

as coals after the fire is banked,

the cardinal in the feeder,

the roses tumbling on the arbor

their weight bending the wood

the red of the syrup I make from petals.

Orange as the perfumed fruit

hanging their globes on the glossy tree,

orange as pumpkins in the field,

orange as butterflyweed and the monarchs

who come to eat it, orange as my

cat running lithe through the high grass.

Yellow as a goat's wise and wicked eyes,

yellow as a hill of daffodils,

yellow as dandelions by the highway,

yellow as butter and egg yolks,

yellow as a school bus stopping you,

yellow as a slicker in a downpour.

Here is my bouquet, here is a sing

song of all the things you make

me think of, here is oblique

praise for the height and depth

of you and the width too.

Here is my box of new crayons at your feet.

Green as mint jelly, green

as a frog on a lily pad twanging,

the green of cos lettuce upright

about to bolt into opulent towers,

green as Grand Chartreuse in a clear

glass, green as wine bottles.

Blue as cornflowers, delphiniums,

bachelors' buttons.

Blue as Roquefort,

blue as Saga.

Blue as still water.

Blue as the eyes of a Siamese cat.

Blue as shadows on new snow, as a spring

azure sipping from a puddle on the blacktop.

Cobalt as the midnight sky

when day has gone without a trace

and we lie in each other's arms

eyes shut and fingers open

and all the colors of the world

pass through our bodies like strings of fire.

The Seven Of Pentacles

Under a sky the color of pea soup

she is looking at her work growing away there

actively, thickly like grapevines or pole beans

as things grow in the real world, slowly enough.

If you tend them properly, if you mulch, if you water,

if you provide birds that eat insects a home and winter food,

if the sun shines and you pick off caterpillars,

if the praying mantis comes and the ladybugs and the bees,

then the plants flourish, but at their own internal clock.

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot tell always by looking what is happening.

More than half the tree is spread out in the soil under your feet.

Penetrate quietly as the earthworm that blows no trumpet.

Fight persistently as the creeper that brings down the tree.

Spread like the squash plant that overruns the garden.

Gnaw in the dark and use the sun to make sugar.

Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.

Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, keep bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,

for every gardener knows that after the digging, after

the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.

MARGE PIERCY (EE. UU., 1936)